Reflections from Myron’s daughter Anji (.pdf)

(or “Hello, I must be going”)

First of all, I think that Myron would have loved to have his Obituary begin this way:

Myron shuffled off this mortal coil on March 28, 2019.

Myron treasured words, he could be quite witty, and he appreciated Shakespeare, so that is how I’d like to start.

Some years ago, Myron put together a lot of facts about his life, at my request, so that I would have accurate information for his eventual Obituary. Myron also told me, more than once, that he feared that he would not be “known.” My mother thinks that this fear may be related to how disturbed Myron felt, when his own father died, that his father’s Obituary was “so short.” It seems to me that Myron’s fear of “not being known” is more likely to happen if he only has a short, factual Obituary; those facts are such a small part of Myron’s story, as is the case for anyone who has lived a full life. Because both “tooting his own horn” and telling embellished and rambling stories with a lot of commentary were things Myron did very often, I decided to write his Obituary in similar fashion. I’m augmenting Myron’s facts so that others can feel that they “knew” him. I’ve elaborated on his facts with reflections and memories, mine and other people’s, and with stories he told me over the years. I’m hoping this version will give a more nuanced picture of who Myron was and what it was like to be in his presence.

Myron Fink shuffled off this mortal coil in the very early morning of March 28, 2019. He was 39 days short of his 95th birthday.

Myron was born in New York City on May 6, 1924. Myron died in Bellingham, WA, in his bedroom at his home on March 28, 2019, with his beloved son Paul at his bedside. He arrived in the spring and he left in the spring. He loved that view out his window, the sky and the trees waving with the wind, until the end.

Myron was the first child of Sarah Kaufman and Leon David Fink. Leon was just a young child when his family emigrated from a small Jewish village along the Russian-Polish border after numerous violent attacks on their village somewhere in Eastern Europe. He couldn’t read or write and didn’t know when he was born but decided to celebrate his birthday on July 4 because he was so grateful to have come to America. I don’t know much about Sarah’s family except that she was born in the US of Polish parents and that her father, Myron’s grandfather, “had a candy store” on the Lower East Side. It’s safe to assume that both of Myron’s parents’ families had experienced violence and anti-Semitism at some points in their histories and felt truly blessed to become American citizens.

Myron was born at Second Avenue Hospital in Manhattan on the first Tuesday in May of 1924. (I looked it up: it was a Tuesday. I also learned that, one year later, New York City’s population made it the largest city in the world with 7,774,000 people.) When Myron was four, seven months after his mother had given birth to his sister Doris, his mother died of Spanish influenza. His father then placed his children with their mother’s relatives, and sometime later he moved Myron to a Jewish orphanage in Manhattan (the Hebrew Orphan Asylum on Amsterdam Avenue, between 136th and 138th Streets).

Myron called the orphanage “the institution.” He did not provide a lot of details about the isolation, neglect, and abuse he experienced there, but when asked about himself he always started there. “My mother died when I was four and I grew up in the institution.” This was the dominant story in Myron’s consciousness, and it haunted him all the days of his life (and in some ways, all the days of his wife’s and children’s lives also).

Paul recalls Myron telling him that Myron was able to get the people in charge there to give him a key to the library. There, he went to escape the intensity and noise outside that room. Myron told Paul that every boy was beaten regularly, and that he was frightened every day. Much of the violence came from the older boys, who kept the younger boys fearful for their safety. His only really fond memories were his annual visits to Summer Camp (in the Adirondacks) where he could finally feel safe, feel free, breathe good air, truly play, swim in the lake, and where children would not get beaten.

Paul remembers Myron telling him that his father visited him at the institution almost every day at the end of his work shift. Myron said that the other boys were incredibly jealous that Myron had a father who was always visiting, while Myron was furious that his father would not get him out of there and begged him regularly to do so. His cousin Sondra recalls that she knew that she had a cousin in the orphanage and remembers that she could look at him through bars of the gate but she was not allowed to talk to him. Myron doesn’t remember seeing her or knowing about her while he was in the orphanage.

Clearly intellectually hungry and gifted and having no one to suggest what he should read, Myron once told me, “I went to the orphanage library and started with A.” He developed a stutter and often went without speaking at all. He made a lifelong friend in the orphanage, a boy named Abe Simon, who was his best man at his wedding and his best friend all his life. (Myron told me this story: “Abe Simon was my best friend at the institution. He used to say, ‘Myron, just talk.’ I’d say, ‘Just talk? But about what?’ He’d say, ‘It doesn’t matter, I just like to hear you talk.’”)

Myron lived in the orphanage for about ten years, at which point the governor of New York shut down the orphanage as unfit for a place to raise kids. Myron returned to live with his father, and he graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx in 1942.

Myron enjoyed telling me about how he and Abe and other boys used to hang out in Manhattan at night loudly chanting this funny refrain:

Football baseball swimming in the tank!

We are the boys with money in the bank!

City College!

City College!

It’s a college?

Myron was a student in the College of Agriculture at Cornell University from 1942-43. If you were to ask, “But how does an impoverished Jewish kid afford Cornell?” Myron would tell you a story reflecting his tactical skills: Cornell Ag school was a statutory college operated by the private Cornell University on behalf of the state. You could go to Cornell and still be a part of the SUNY system, and Myron played the system, not particularly intending to stay in the Ag field but wanting to find a way “in” to the Cornell, Ivy League, system. He loved reminiscing about the field experience he had one summer in upstate New York where he was placed with an anti-Semitic farmer. Myron said, “I decided to tell him that I was a Lutheran. I have no idea why I chose Lutheran!” When Myron told this story, he laughed and laughed, repeating, “A Lutheran! Can you imagine? A Lutheran!”

Myron served in the US Army from 1943-46 (where he saw action with the 103rd Infantry Division in France, Germany, and Austria). He didn’t share much with us about this time in his life except for a few particulars: that on some bitter cold mornings, with no tent or sleeping bag and only one wool blanket to sleep in, he couldn’t open his eyes because his lashes had frozen shut, that it was during this time that he developed a loathing for Spam, that they burned leeches off their bodies with matches, and that he envied the guys in the Navy because “they got showers!” When Myron saw that the medics in the army had a much easier time of it than the infantry, he told someone there that he was planning to go to medical school after the war, and I think that he then got assigned as a helper in the medical areas.

When Myron returned from Europe, he went back to Cornell on the GI bill: this time to the College of Arts and Sciences. He graduated with an A.B. “with distinction in Philosophy” in 1948. While at Cornell, Myron took every course in Philosophy that was offered, including all the upper level ones that were usually for grad students. Here’s a story where I probably have some details wrong (he told me this in 2011): “I decided to major in philosophy because of this guy, Tommy Durkin, who was an air artillery ROTC in 1942. He was a graduate student in philosophy at Cornell. While we were in the army, he used to sneak off the base. I asked him ‘What do you do when you sneak off?’ He says, ‘I fuck off.’ (lots of laughter) I fuck off! He’s the reason I majored in philosophy. He taught me Plato and Aristotle in 3 months.”

Myron then studied at New York Law School from 1948-51 and earned his LL.B. “Cum Laude.” He was admitted to the Bar of the State of New York in 1951. He practiced law in the firm of Morris Diamond in Queens for the next several years and later worked as a Court Attache in the Court of General Sessions in Manhattan.

Here’s another story Myron told me many years ago about his mental health challenges in his 20’s:

While he was in college (post-WWII), Myron gradually withdrew, finally couldn’t take exams, and was excused because of help from a psychiatrist at Cornell who kept saying, “Hold on – just hold on a little longer.” He was referred to a psychiatrist at Bellevue in NYC named Martin Stern. Myron called him “Stern.” Myron said he didn’t talk for a year: he typed letters which Stern then read while with Myron. Myron saw Stern for 7 years. He remembered these two things Stern said: “There’s nothing inconsistent about you” and “You’ve learned academically but not emotionally – you have a lot to learn.” Myron paid Stern with a $10 bill at the end of each visit.

At the end of telling me this story, Myron said, “Six years later I introduced him to my fiancée. He was delighted.”

In early 1955, Myron was fixed up on a blind date by a friend and met a young social worker, Elka Myra Person, who had come to the US from the Netherlands in 1939 and had grown up in Great Neck, Long Island. Elka thinks that she told her mother after their first meeting, “I’ve met the man I’m going to marry.” Elka introduced Myron to A.A. Milne, and they read Winnie the Pooh together in Central Park in the spring of 1955. Three months after meeting, they married on May 8 in Elka’s parents’ apartment on Central Park South. This man, heartbroken so early, found himself a gem.

Myron often said that marrying Elka “was the best thing I ever did.” The couple settled in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, and Myron began studying to become a professional law librarian at the School of Library Service at Columbia University. Upon his graduation with an M.S. in Library Science in 1957, the couple moved to Los Angeles, where Myron was employed as Reference Librarian in the UCLA School of Law. A year later, he accepted a position of Law Librarian and Assistant Professor of Law at Loyola University Law School. There he taught Legal Research and Writing, Legal Bibliography, and Legal Writing. He remained in this position for five years, during which time he earned a Masters in Law degree (LL.M.) “Magna Cum Laude” from New York Law School. His Masters thesis, “Research in California Law,” was later published and used by students in various law schools in California.

Here’s where I’d like to take a moment to look back at all the ways that Myron’s intellect, hunger for words, fierce survival instincts, calculated decisions, and luck in meeting kind and helpful people along the way, make his a story of triumph rather than tragedy. His cousin Sondra, who met Myron in his post-orphanage days (long after she had watched him through the orphanage gate in her childhood) fondly remembers Myron and his friend Abe visiting and taking care of her “as a single woman” in the city. “They were my benefactors,” she recently said to me. And with great affection and awe, she added, “It was amazing what Myron accomplished in his lifetime.”

During their time in Los Angeles, Myron and Elka had two children, my brother Paul in 1958 and me in 1960. In 1963, our family moved to Albuquerque, NM, where Myron accepted the position of Law Librarian and Associate Professor of Law at University of New Mexico. During the next 27 years, Myron developed what many considered to be the finest Law School Library for its size in the southwest. It became the legal reference center for the state of New Mexico and served as the local bar law library. Myron taught courses in Legal Research and Writing, Equitable Remedies, Remedies, and Injunctions. For many years and up to the year he retired, Myron taught an innovative seminar in Law and Social Change for third year students which was critical and challenging and very popular. His published writings include “Good Books for Law Students,” an annotated selection of outstanding books for law students.

Here’s another story where I may have some of the details wrong but it’s mostly accurate: There was apparently a humor magazine published at UNM in the early 1960’s, and the writers of the magazine had conjured up a fictional character and given him the funniest name they could think of. Myron was hired at the law school around this time, and then an article was written with the headline “Last Laugh Is On The Staff.” Apparently this character had been named Myron Fink.

Myron became a committed Socialist while in college and remained one for the rest of his life. While a professor at UNM, Myron was the New Mexico state chairperson of the US China Friendship Committee, a national group in the US supporting Mao Tse Tung’s Cultural Revolution in China. He was active in the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Lawyers Guild (he led the Albuquerque chapter).

Myron loved nature, and the family regularly visited national and state parks for summer holidays. One summer, we visited Grand Tetons, Yellowstone, Glacier, Lake Louise, Banff, and the ancient forests of the Pacific Northwest. It’s likely on this trip that his son Paul became so enamored with wilderness – a love he still has. While camping, Myron often told us stories in the tent and worked in the line “and they ate succotash, pinto beans, and spinach” wherever it might fit.

Food was an enormous part of Myron’s life. He shoveled food into his mouth without noticing it, probably because he grew up competing with many children for the sparse food offered at meals. He identified strongly with Dickens’ Oliver Twist. For someone focused on food, Myron married the right woman. She kept him in delicious meals for almost 64 years, and he loved to say “Call me anything but late for supper!”

Some related stories about Myron and food:

When I was growing up in Albuquerque, he fed my dog, Shadow, underneath the table like a naughty child, and he had no interest or skills in training her in any way. He proudly pronounced her a “rogue dog” – probably vicariously enjoying her unwillingness to walk on a leash and her rebellious nature.

When Myron was still driving and independent, Todd remembers running into him at the Food Coop and seeing Myron looking very guilty and holding something behind his back. Myron told Todd that he sometimes kept the change from something Elka had asked him to buy and then bought himself a chocolate bar, and that he was “trying out different chocolate bars every time I’m here, but please don’t tell Elka.” Elka recalls that whenever they would shop at the Coop together, Myron would casually help himself to the grapes and cherries on display, which was very embarrassing for her.

In his last years in Bellingham, Myron made several trips to the kitchen in the middle of most nights, snacking on heated milk and pickled herring and peanut butter and mandarin oranges, often washed down with Newman’s Lemonade. He often sought out other treats that Elka had forgotten to hide from him.

Speaking of good food, I’d like to thank Nicole Carter of Bellingham Technical College’s Café Culinaire for always including Myron’s birthday celebration in their jam-packed May schedule. She said to me once, “It wouldn’t feel like May without having your dad here for his birthday.” We loved our annual 3-course meal there and felt so lucky to get in!

We grew up hearing Myron repeat certain stories and quotes, and he especially loved Marx Brothers and WC Fields movies and the radio comedy team Bob & Ray. Elka remembers Myron telling her that his childhood friends frequently went to the movies with him mainly in order to hear him laugh. Thanks to the magic of Youtube, one can hear these bits again, and I’m including links to some. If you listen, please try to imagine Myron ROARING with laughter alongside you, no matter how many times he had heard these routines before. Shaking with laughter, repeating the lines, and even crying from the joy of how funny he found these bits – imagine that as you listen.

Reuniting the Whirleys:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYvBWNdiFiU

Wally Ballou at the Paperclip Factory:

The Komodo Dragon:

Myron would sometimes say goodbye to us with:

Write if you get work, and hang by your thumbs!

(Bob & Ray)

Or he’d sing:

Hello, I must be going, I came to say I’d like to stay but I must be going…

(Groucho Marx)

Myron was the typical 1960’s middle class dad who had a 9-5 job, but what was probably not so typical was how often he came home and lay down on his bed, his room dark, before dinner. Elka sometimes asked me to go in to visit him and “cheer him up.” This was before things like “clinical depression” were named or considered in the way that we think about them now.

In the 1970’s, in another effort to heal from his childhood pain, Myron joined the Re-evaluation Counseling (also known as RC or co-counseling) community, and he participated in this community in Albuquerque for many years. He made a few good friends within that community, one of them Farrell Brody, also an academic at UNM, who recently wrote me, “I greatly appreciated Myron’s wit and intelligence, and we met weekly for lunch and to talk about all kinds of matters, including our past experiences, being Jewish, Israel and Palestine, and many others. I was sad when they moved away from Albuquerque. I saw in Myron a kindred spirit.”

One of the most vivid memories I have of my Albuquerque childhood is frequently hearing the muffled sounds of talking and crying (and sometimes very distressed crying) from the den where Myron was meeting with his co-counseling partners. Elka, Paul, and I were very aware of Myron’s emotional suffering, and this took a toll on us in different ways.

In terms of other pieces of Myron’s Albuquerque life while I lived with him, these are a few other snippets:

We lived in a ranch home that was identical to many others in the neighborhood, a “Mossman-Gladden” home that was very popular in Albuquerque. Myron found the house by driving around and actually seeing a man pounding the “For Sale by Owner” sign into the ground.

Myron loved the TV shows All In The Family and Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In.

Myron didn’t know the names of most of my friends when they came over, which was embarrassing to me. As I understand him now from a very different perspective, his level of distraction and distress prevented him from being able to participate much in my world.

Myron encouraged me to think about going anywhere I wanted for college; he said that money should not be a factor in choices about education, and he was incredibly supportive of my dreams to go to school on the East Coast.

Myron also took a sabbatical in 1974, and our family lived in Ithaca, NY for a semester while Myron enjoyed revisiting the Cornell campus.

Myron experimented with a mustache for a few years, and I think he also smoked cigarettes for a little while!

In 1994, Myron and Elka moved to Bellingham to be closer to their children and grandchildren. For the first decade of their time here, Myron continued to struggle with bouts of severe depression and anxiety. In 2005, having run out of other options, Myron began Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and this was the only thing that ultimately helped him out of his otherwise intractable depression. Post-ECT, I experienced Myron as more present and appreciative. Our family wants to thank Dr. Caty Strong and Dr. Hank Levine for their support and compassionate care over many years.

It’s my guess that those years of ECT probably caused Myron’s later short-term memory impairment. His long-term memory was intermittently sharp until the end. He had an extensive vocabulary, and he sometimes answered questions about history and law just moments after he appeared to be asleep in his chair.

Myron’s three grandchildren called him “Opi.” In his role as Opi, Myron attended lots of their soccer games, plays, music recitals, and living room performances. He wrote sweet notes to his grandchildren, often signed with a little bunny. He also wrote them stories. He really enjoyed being with young children because in many ways he was still very much a child himself and because he valued the experience of childhood he never got to have.

As much as Myron struggled with mental health issues, for more than two-thirds of his life he was in the company of Elka, who loved him, listened to him, fed him, and comforted him. We’re grateful to Abe Simon and to “Stern” for protecting this fragile, sweet man until he could find Elka. Without them, I don’t think there would be a story here at all, and certainly not such a long one.

In his retirement years in Bellingham, Myron pursued many interests including gardening (he took the Master Gardener training and he had all of the grass pulled up in his front and back yard and stuffed more plant material in those spaces than one could imagine), both mediation and meditation, and progressive politics; he was active with the Rainbow Coalition and Whatcom Peace and Justice Center and joined a political book group in Skagit county. He was said to be “a delightful although occasional presence at Quaker Meeting.” He was an active member of the Bellingham Community Rights organization, “No Coal!” (that his son Paul was instrumental in helping to launch), that worked to pass a local ballot initiative to stop the coal trains through Bellingham. He was a prolific reader of socially and economically radical non-fiction magazines and books, which had a profound impact on Paul who began to pay attention to these ideas in his high school years and was radicalized by them. He enjoyed many happy hours doing watercolor and writing poetry. He watched Rachel Maddow and Keith Olbermann every night with great interest. Myron loved walking at Lake Padden, Whatcom Falls Park, and Boulevard Park, and in his last years he loved sitting in a chair in his driveway in the sun.

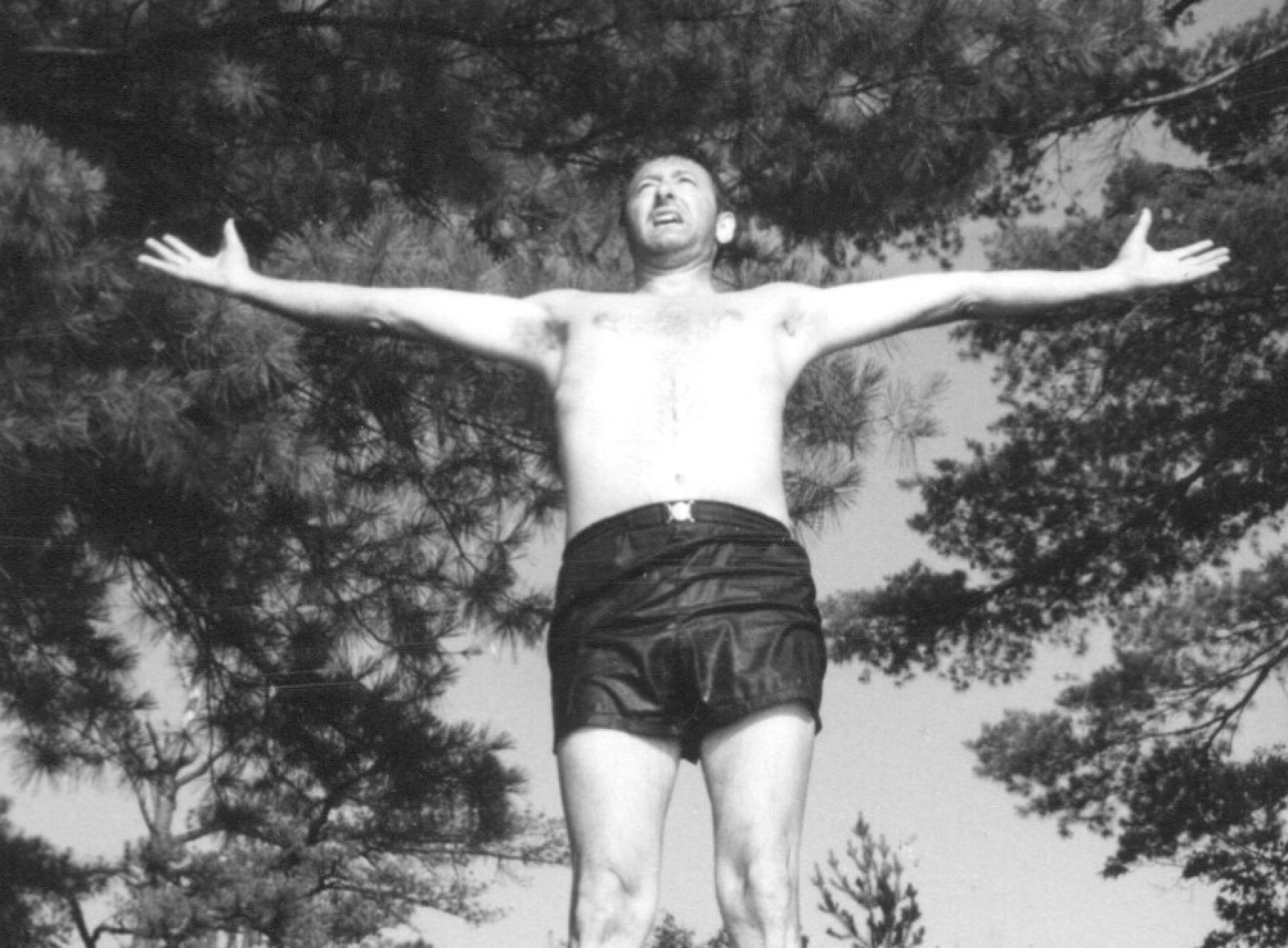

Myron rarely missed a day of jogging several miles (during many of his years in Albuquerque), swimming (daily both in Albuquerque and Bellingham), and stretching daily in an elaborate ritual on his bedroom floor. Undoubtedly this physical exercise (accompanied by Elka’s healthy meals) was a factor in his long life and health. In the last years of his life, Paul Mulholland helped him keep up his physical strength, and we thank Paul for that care. Myron’s memory was deteriorating over the last ten years, but his physical body was in spectacular shape until the very end.

Some years ago, Myron had a car accident on Chuckanut Drive where he drove into a ditch while changing the station on his radio. The accident luckily happened on the rock side of that road rather than the view side. This episode culminated in our family’s decision that he should no longer drive. We were able to convince Myron that rather than get his car fixed, he should stop driving, and once he could see that we weren’t going to budge from that position, he admitted that the accident had happened because he “had forgotten that he was driving,” and then he began to enhance his story with confessions like, “I hit poles and gas pumps all the time! Have you noticed all the scratches and dents in my car?” and as we laughed, so relieved that he was accepting our decision, he continued to confess outrageous incidents he had experienced in his car.

Once he was no longer driving, Myron rode to the pool with WTA Paratransit, and the drivers were exceptionally warm and helpful. Our family wants to thank these lovely gentle people for all their good care and safe transporting of this man who, even when he didn’t always remember where he was going, always enjoyed his swim once he arrived there.

Myron had a beautiful reading voice, and we loved it each time it was his turn to read at our yearly Seder. When I complimented him once, he told me, “I love language. When I see a word that needs attention, I give it attention, and as a result, I read well.” Giving words attention, delighting in language and reading and writing, loving stories, and valuing education are all things I’ve inherited from Myron and greatly appreciate. At his bedside a few days ago, I read Myron his favorite Sonnet 73 from Shakespeare several times, and he listened intently. It was clear to me that inside his head he was reciting it along with me.

Myron felt loved and valued when he was listened to, and once he warmed up he could go on and on and on, expounding and reminiscing whenever he sensed an audience. I’m glad Myron had an early, loving audience in Abe Simon. For Myron, I think that his words were a way to try to satisfy his deep emotional hunger to feel whole and not so alone. His sweet poetry, some of which is included on this website, was another way he showed his facility with and love for language.

Speaking of loving an audience, Myron was in the very first Bellingham Children’s Theatre production: Drue Robinson Hagan’s “The Soup Kitchen” in 1994. Earlier in his life, he played Santa Claus in a play I don’t remember anything about, he performed in the UNM Law School’s production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Trial by Jury” (even though he sang very poorly), and he used to talk about being the prince in a high school production of “Cinderella” which was all in French (he didn’t speak French, so the idea of him starring in this play strikes me as odd, and I sort of question it, but he loved to laugh as he told this story, repeating and then undoubtedly exaggerating the details). Thinking about his singing voice for a moment reminds me of another story he used to tell: “When I was in a school chorus class, the teacher said, ‘Sing this note’ and played a note on the piano. I sang that note but she said, ‘No, you’re not singing the right note,’ and I told her, ‘You’re not playing the right note!’”

Myron loved flannel shirts. He liked being comfortable; he made no pretenses. The only jewelry he ever wore was his Cornell ring with the red gem. He mostly lived in his head, in the intellect, in the realm he could master. He sometimes had Big Ideas and Big Plans. Apt adjectives describing Myron or experiences of Myron in his various states would include loyal, verbose, thoughtful, infuriating, scary, highly suggestible, sharp-witted, grandiose, despairing, inspiring, naive, loving, silly, inconsolable, exhausting, expressive, intense, embarrassing, funny, demanding, playful, unpredictable, uncensored, explosive, whimsical, inappropriate, ever-searching, melancholic, generous, self-centered, awkward, absent minded, wise, moody, sentimental, meek, responsible, oblivious, childlike, and sweet. How does one reconcile all these disparate experiences with one’s father?! Just making the list has conjured up so many other stories…

As I’m hoping I’ve been able to express, Myron was a multifaceted guy. His attention was mainly to himself. A paramedic responding to his fall (which precipitated his death 6 weeks later) said, after doing a mental status, “He’s oriented times one, to himself,” and I found this interesting because this was the way I experienced Myron most of my life. He was a troubled and remarkable man, extremely challenging to have for a father. I know that he did the very best he could, and now, as I’m saying goodbye to him and sifting through memories and photos, I find myself rewriting and romanticizing the story of my life with Myron. Maybe that’s typical. As an adult, I came to understand Myron in the context of where he came from, I feel grateful for all that he was able to provide, and I am touched when I reflect on the ways he trusted us to take care of him. I think that his is a tremendous story of triumph over adversity. The family he created for himself, and the family I then created in addition, has been devoted to him our entire lives.

With this tome, I hope that I’ve succeeded in helping others feel like they truly “knew” Myron so that his fear is not realized. It means a lot to me to try to offer this last kindness to such a complicated human being. I hope that none of what I’ve written feels disrespectful to the memory of Myron; I believe he’d agree with everything I’ve said here (and jump in to add even more stories), although I’ve almost certainly botched a few details. He did enjoy being the center of attention.

I love the concept that, in death, we are reunited with loved ones who have already died. It comforts me to picture Myron now back in his mother’s arms.

Myron’s relationship to Judaism was ambivalent. I assume that he associated the suffering and despair of his early life with a Jewish orphanage. He was Bar Mitzvah’ed as part of being in the orphanage. After having no interest in practicing Judaism while raising his children, he joined Albuquerque’s Temple Albert (with Rabbi Paul Citrin, whom he liked very much) and then joined a Hebrew school class of adult learners. Anyone reading this who feels moved to say the Mourner’s Kaddish for Myron should know that this ritual would be meaningful to me and possibly also to Myron.

Paul Robeson sang, in one of Myron’s favorite songs, Old Man River:

I’m tired of livin’

But scared of dyin’

My sense is that this was exactly how Myron felt at the end.

Myron is survived by his wife of almost 64 years, Elka Fink, of Bellingham; two children: son Paul Cienfuegos of Portland, OR and daughter Anji Citron (and husband Todd Citron) of Bellingham; three grandchildren: Julia Citron (and husband Kareem Farooq) of Kirkland, WA; Ezra Citron of Seattle, WA; and Noah Citron (and wife Rachel Santiago) of Portland, OR; one great-grandson: Jasper Citron of Kirkland, WA; sister Doris Gordon of West Hills, CA and her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren; first cousin Sondra Blum of Seaford, NY; and numerous loving friends.

Myron’s body will be used for research by the UW Willed Body Program, and anyone interested in this program can see details here: UW School Of Medicine – Willed Body Program.

Some more thank you’s from Myron’s family…

– To Elka’s community of friends for all of their support of her over these last challenging years and for helping her get occasional respite by keeping Myron company.

– Stephen Ware for his vigilant care of Myron and Elka – above the call and duty of even the best neighbor that anyone could ask for.

– To Bellingham At Home, who has helped Elka get respite over the last two years.

– To Mark Lindenbaum, MD, Myron’s doctor for many years.

– To Serge Lindner, MD, Myron’s doctor for his last years.

– To Laura Curtis, ARNP, Myron’s health care provider for a brief time near the end.

– To Jen Bauer of Shuksan Rehab, who helped us navigate Myron’s care in two separate stays and who was incredibly accessible and generous with her support and advice, even on weekends.

– To Dale Nakatani, Gabby Fink, and other staff members of Shuksan Rehab for their patience and good care.

– To all of the incredible Whatcom Hospice staff.

– To our personal “team” of Shelli Bernard and Bobbie Kinkel who supported our family so lovingly for Myron’s last few weeks. An intra-family thank you to Ezra, who came home to take care of his Opi for 8 days at the end of his life. Myron was terrified that he would die “in an institution.” Thank you so much, all of you, a heartfelt and enormous thank you, for being available so that Myron could die in his own peaceful bedroom with his familiar Paul Citroen tree and Charlotte Stadler flowers on his bedroom walls.

– Over her 90 (and counting) years, Elka has cultivated an incredible collection of friendships, and Myron benefitted from these as well as nurturing a few special ones of his own. Tom Hall may have been his closest Bellingham buddy, and Joyce Pacher was also a very special presence in his life and is still an essential one in Elka’s. Thank you Joyce, for all your care of these two.

Here’s what Myron said to me on his 87th birthday:

“I woke up today with thoughts about how it’s in layers: First, I’m alive, breathing, and that’s great. Second, it’s so much about luck, not anything I did, and if anyone had told me I’d be in this 87th birthday position when I was younger, I wouldn’t have believed it. Third, it’s all about family: I’m surrounded by good people; I did so well for myself.”

I agree.

In 1955

My father, lost

Was found by

My mother.

She read him Winnie the Pooh in Central Park

Because his mother had died when he was four

And he had never met Pooh or anyone else like that.

He said

Marrying her was the best thing I ever did.

55+ years later, my father, in so many ways, is still lost.

My mother, though tired of both his voice and his blindness to the world outside himself

Still chose

When we took them on a trip back to New York last autumn

To pack Winnie the Pooh in her suitcase.

They found a bench in Central Park

And read to each other

As the orange and yellow leaves fell around them.

~ Anji Citron (2011)

If you’d like to do something in Myron’s honor, you may contribute to one of these organizations:

Whatcom Peace and Justice Center

And know that any time you give attention to words, marvel at this astonishing and gorgeous planet, pursue social justice, protect the innocence of children, or tell a very long story that goes on and on and on, with lots of exaggerating and laughter, you are honoring Myron Fink.