Reflections from Myron’s son Paul (.pdf)

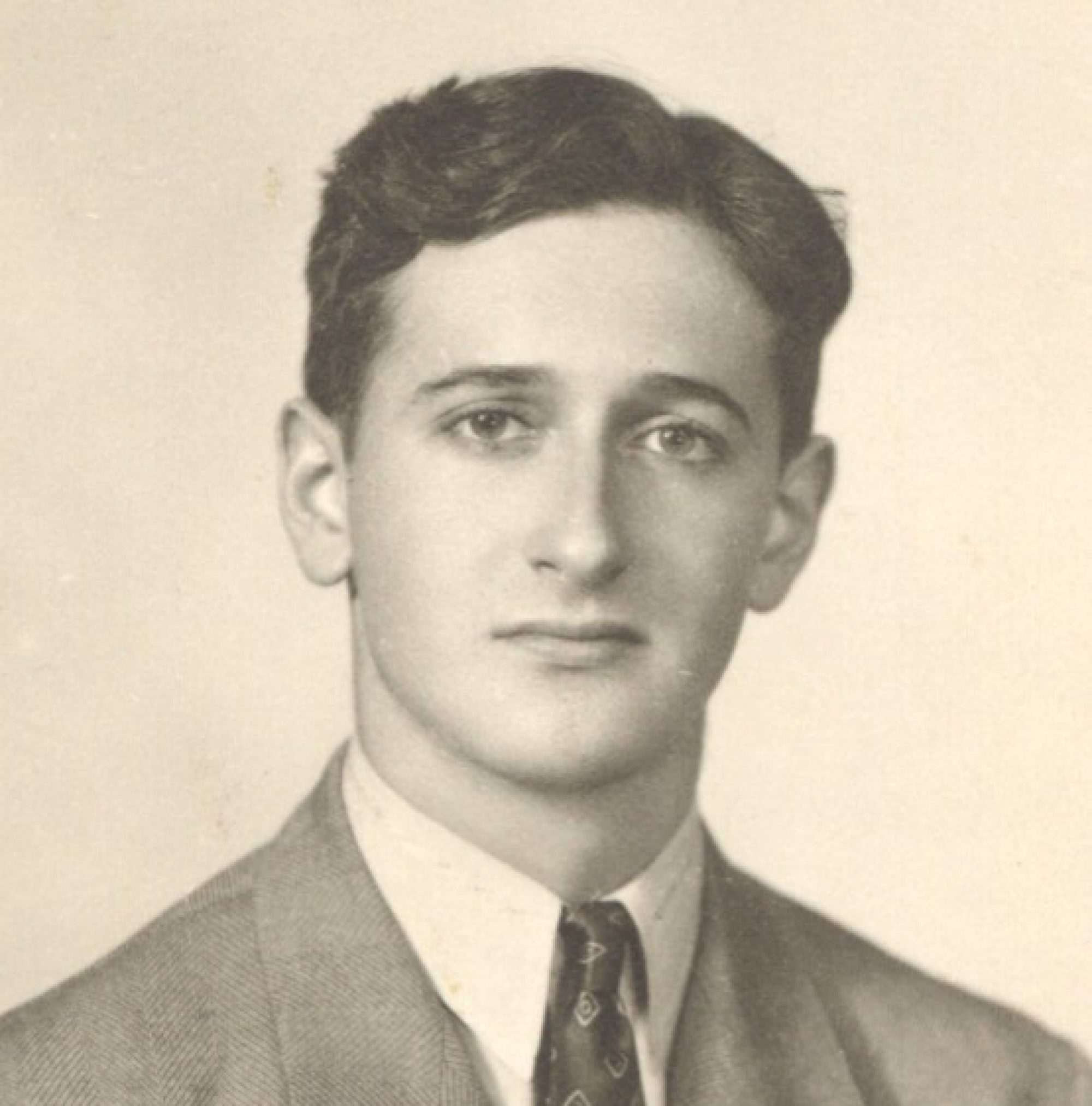

My father was a very special wounded man. He was real. He was genuine.

As a child growing up in Albuquerque, I wanted a Dad who could help me build a clubhouse for myself in the backyard, or a piece of wood furniture. He could barely hammer a nail. So I had to lead the two of us through all of the steps necessary to make this happen.

As a young teenager, I wanted a Dad who could take me backpacking into New Mexico’s many wilderness areas as I was still too young to drive. He was terrified of the prospect of us getting lost, of his son getting hurt, of being attacked by wild animals especially once it got dark. So I had to lead the two of us through the numerous steps necessary to pull this off – from shopping for the right gear, to researching trails, to actually making it all happen. I mostly had a great time in the backcountry with him, whereas he would usually report to family that it was scary and hard, as soon as we returned home.

I most remember the Pecos Wilderness where I discovered at our campsite (six miles in) that he had carried a heavy carpenter’s hammer in his backpack in order to knock the tent stakes into the ground! And White Sands National Monument, where we fought off hypothermia all night in cotton sleeping bags while hiking across the sand dunes in Winter. And a mountain wilderness with a wild river that ran warm, a few hours east of San Diego, where he later reported to our family that I almost died, when in fact I had only sightly injured my ankle on the hike out. He was a real sport, and did his best to show up for me when I needed him to, even if it was WAY beyond his comfort level.

One summer during my college years at The Evergreen State College in the late 1970’s, I invited him to travel the west coast with me, to visit a number of intentional communities (then still referred to as communes I think). We both had a curiosity about them, and he held a fantasy of living in one some day in the future. I already knew then that it was pretty weird to invite your father to do a road trip with you visiting communes, but that’s the relationship that we had at the time. And I loved it.

We traveled together from Northern California to Vancouver, Canada. Sometimes we hitchhiked. Once we waited most of a day to hitch a ride in the middle of nowhere in Humboldt County, CA (where I later lived!) – me with my long hippie hair and bright clothing, him clean shaven and plainly dressed – as cars sped past us on Highway 101. We were probably too freaky a pair for anyone to trust stopping for! Finally we gave up and hiked about three miles to Garberville and caught a Greyhound bus heading north.

Dad had a blast visiting these anti-establishment communities, sometimes even more than I did, and the people we met there loved him to death. That summer, for the first time, I truly saw my Dad as someone who had chosen to lead a very conventional life with a professional career that could support a nuclear family, but who might very well have been happier as a free spirit, untethered to conventional societal commitments of work and family, if he had not had such a traumatic childhood.

Some years after I graduated from college, but still living in Olympia, WA, I decided to change my last name, as I had always hated the name Fink and was endlessly teased about it as a kid. I remember well a dinner I had with my parents at a Chinese Restaurant on a visit home to Albuquerque. It was there that I broke the news that I was to become Paul Cienfuegos. I remember both of my parents were initially in shock. I remember my father sharing his sadness that Anji had already decided to give up her last name when she married. And so with my name change, the name Fink would no longer carry into future generations. He told me how sad that made him feel. And then just minutes later, still at the restaurant, he was done with his own internal grieving, and told me that he would welcome my new name, if that’s what was important to me.

I remember something of a similar nature happening a year or two later – when I admitted to my parents that I thought I was not going to become a math teacher or a lawyer, as my father had dreamed, but instead I was moving more and more in the direction of a much less financially certain future as a social movement person. As a community organizer. Social change work had become my passion throughout my college days, and it seemed to be the thing I most wanted to continue doing. Again, my parents were concerned at first. But then they both really showed up as my supporters, as I dived more and more deeply into long-term campaigns to stop clearcut logging on Vancouver Island’s wild west coast for five years, to lead Joanna Macy’s groundbreaking workshops in Britain for three years, and to train hundreds of people to participate in nonviolent direct action at the Trident Nuclear Submarine Base west of Seattle for a series of mass actions. My Dad would sometimes even show up for the event, once my parents had moved to Bellingham.

Ultimately, my father became my biggest fan. I think I took that for granted for many years, but it did finally sink in as to what a big deal that was, to have a university professor father cheering on his increasingly radical son who simply wanted to change the world and truly believed that he could. And perhaps I truly believed this because my father was right there at every step of my young adult years, making sure I knew that I had his support.

When I became involved in the Community Rights movement in the early 1990’s, my father played a role in helping to mobilize the Bellingham activist community so that I could be invited to lead a workshop there. It was very well attended, and from it came a core group to carry this campaign forward. Ultimately, he helped to create the ’No Coal Trains!’ group, regularly contributed to its newsletter, and attended its organizing meetings. And finally having a social change project that we were both involved with was a big treat for me, as we then had even more to talk about!

My father (and mother) also had really big blinders on for much of my childhood, regarding my pleas with them to get me out of certain schools where I was being terrorized by other kids and some teachers also. And I still remember the day my Dad wouldn’t let me sit on his lap anymore (I must have been all of six at the time!) because big boys aren’t supposed to sit on their father’s laps. Augh! Amazing what we still remember many decades later!

As my Dad became an old man, his life-long battles with anxiety and depression worsened again. He was helped by treatments from his psychiatrist, but after that he entirely lost his capacity to be engaged in the world as a social movement person. He went from being a voracious reader to not reading at all. He went mostly quiet. I rapidly lost the father I had so counted on for so many years. Of course, this is how life is. Big transitions are part of the fabric of our lives.

I have continued to visit my parents often in their elder years. I so wanted to be present for his death. And on the night that he died, I had arrived by Amtrak less than three hours earlier. It was truly a blessing to be sitting with him when he literally breathed his last breath at 1:13 am on March 28th.

My father was a very special wounded man. There was much that I needed as a son that I never got. And in other ways, he was an amazing Dad. I have lived the first 60 years (!) of my life with two parents. It’s a total mystery for me how these next years will unfold as an almost-elder myself, and finally fatherless. The adventure continues…